Synopsis

A simpler version of the book, right here!

Mind Beyond Matter can be a difficult book to get through. Here you will find the theory in as simple terms as possible. I will spend a minimum of time on the physics, moving on as quickly as possible to consciousness and psychology. If you really don’t want to read any physics that’s fine – you can skip forward to Chapter 6.

To be ultra-succinct, this theory says that your mind, and your emotions, are fuelled by two types of head-space. One head-space is constructive and the other destructive. These nonmaterial mental energies are unrecognised by science because they cannot be directly detected with material instruments. This model is supported by a large amount of scientific evidence, and I cannot find any evidence to refute it. The model also offers solutions to the majority of unanswered ‘big questions’.

Chapter 1 – A different kind of space.

Dark energy has been a part of our standard model of the universe for the past 25 years. It is not matter because it behaves differently, anti-gravity, expanding space in an exponential fashion. It can’t been seen directly, only by inference. It is considered the first nonmaterial substance identified in the universe, and it appears to be everywhere. That means it is also in you and me.

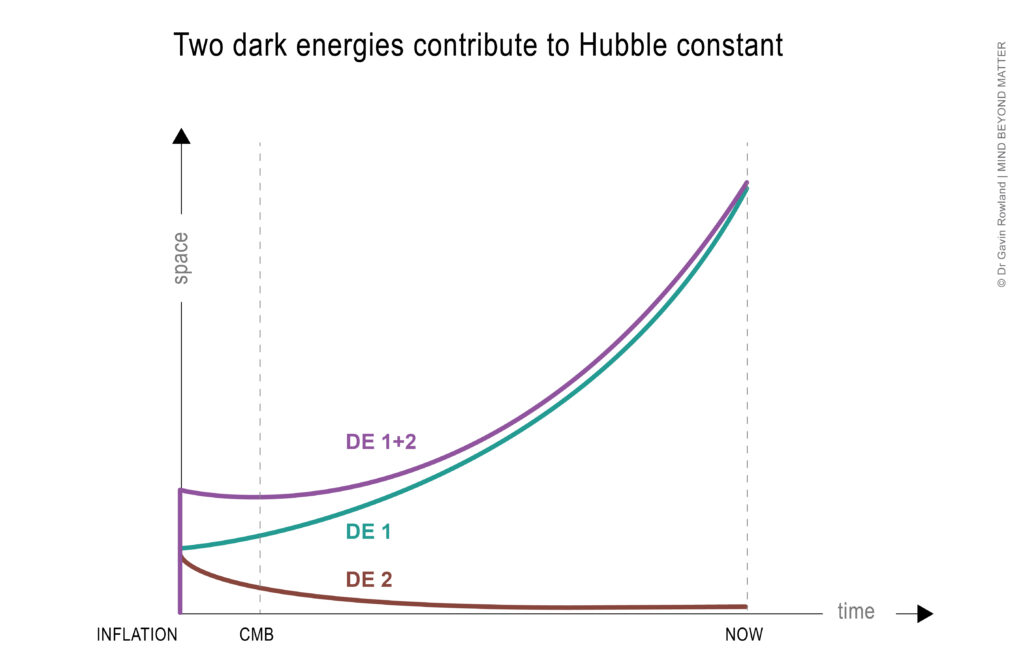

The universe has been expanding continually since the Big Bang. Because of the dark energy, this expansion is accelerating. Currently (2023) a major controversy in cosmology is the discrepancy between the early measure of the universe’s expansion rate and later measures. The expansion rate of the universe is called the Hubble Constant, so this discrepancy is referred to as the “Hubble tension”. There are quite a few news clippings about this on my Facebook page. In Chapter 1 of Mind Beyond Matter I referred to it as the “late takeoff of dark energy” problem. At that stage it was only a potential problem but since then a huge amount of evidence has been gathered and it is regarded as the biggest problem in cosmology.

The trouble is, the data were supposed to follow the green line, marked DE1 in the above diagram. But the data are showing that the expansion is slower at the time of the CMB, which is more a fit to the purple line, which I have labelled DE1+2. What I predict is that there is a second dark energy, the red line, which trends towards zero. Add the two dark energies and you get the net effect. This is what I propose is upsetting the results of the early measures of the Hubble constant.

Cosmologists haven’t hit upon this explanation. There have been various proposals about the behavior of dark energy, many being along the lines of an “early dark energy” which is expansive (like the usual dark energy) but only kicks in briefly in the early universe before withering away for some reason. This has since become the favorite approach to the problem. Researchers are focusing on it as something with “exotic properties” that make it “decay” (i.e. disappear) in order to then allow the universe’s expansion to proceed as normal. Early dark energy seems to me a rather ad hoc solution and creates its own questions – why did it appear and why did it disappear? Expanding the Universe with another force in its early times is also problematic because it spreads the large scale structure of galaxies and galaxy clusters further apart, when the evidence is currently saying that the standard model of cosmology doesn’t cluster things together enough. A dark energy that pools out and contracts may prove a simpler solution. It would slow the dark energy expansion early, but naturally withers away as it shrinks to smaller volumes, and it helps the galaxies and supermassive black holes form faster.

Why would the contracting dark energy pool out? In the book I proposed that DE1 and DE2 units separate at the Big Bang via a process known as inflation (another unexplained feature of our standard understanding of cosmology). This is also illustrated on the diagram above, where the total volume of DE1 + DE2 jumps up at the beginning of time. Inflation behaves very much like dark energy, but is a lot more powerful. Mainstream cosmology has attempted for years to demonstrate inflation to be a property of matter but the results are unconvincing (unless perhaps you are a fan of the multiverse). The process of inflation proposed here would result in pools of contracting dark energy coalescing within a greater ocean of expanding dark energy. This pattern of contraction would need to be an exponential of decreasing curve as it should never contract to zero (this would probably violate the law of conservation of energy). An exponential contraction of these pools of DE could initially be quite a powerful pro-gravity factor, resulting in accelerated collapse of the primordial soup of matter and energy within into black holes and galaxies.

This leads us to the other emerging controversy I pointed out in chapter 1. That is, that supermassive black holes appeared too early for our current “standard” model of cosmology. Gravity alone probably isn’t strong enough to push this process along quickly enough, and it would appear as if black holes actually collapse directly, rather than the expected process that involves massive stars going supernova. More data is coming out regarding the early growth of supermassive black holes (see Blog).

So there are three major cosmological questions – inflation, the discrepancy in the expansion rate and the early appearance of supermassive black holes – and all are now on the table and unexplained by the standard model. My explanation covers all three and I think it is correct. Further updates may be found under Blog.

Chapter 2 – Something from nothing.

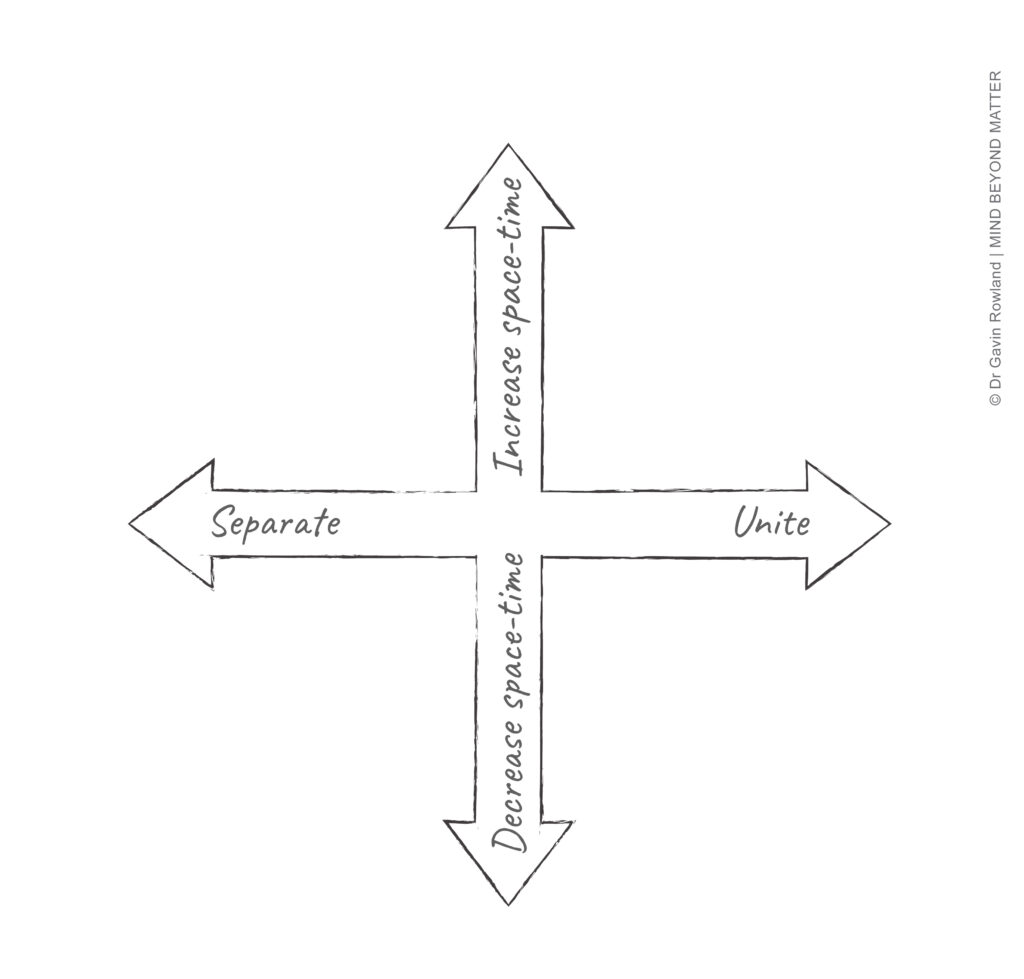

In this model of the universe we have two nonmaterial energies, one of which contracts towards zero space and the other which keeps expanding towards infinity. Now rather than just talking about space, let’s be more correct and talk about spacetime. Einstein taught us that because of the invariant speed of light we live in a 4 dimensional spacetime – one dimension of time and three of space. Relativity experiments show us this. So dark energy 1 is in fact building or expanding spacetime and dark energy 2 is shrinking or contracting spacetime.

The funny thing is, when we look back at matter, it has the same two properties. If we imagine a bunch of energy, in the form of the early universe (a hot pool of radiation and gas) in a zero gravity environment, it will go on expanding indefinitely, seeking a state known as thermodynamic equilibrium, where it achieves maximal expansion. If there is no boundary, this will go on forever towards infinity. Although many would argue that spacetime just is, I would argue that because energy creates light and motion, it can be credited with creating spacetime. And gravity is like DE2 – it will shrink spacetime to ever smaller dimensions, moving forever towards what is known as a spacetime singularity.

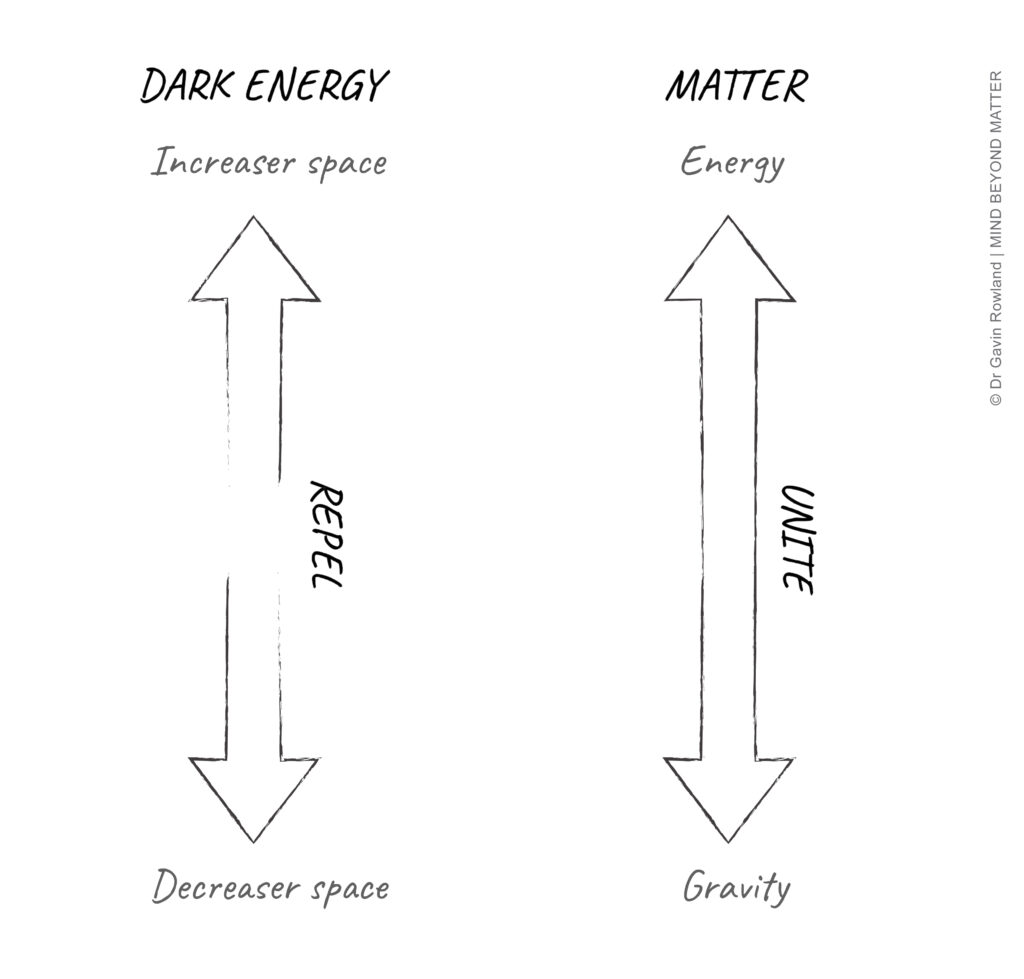

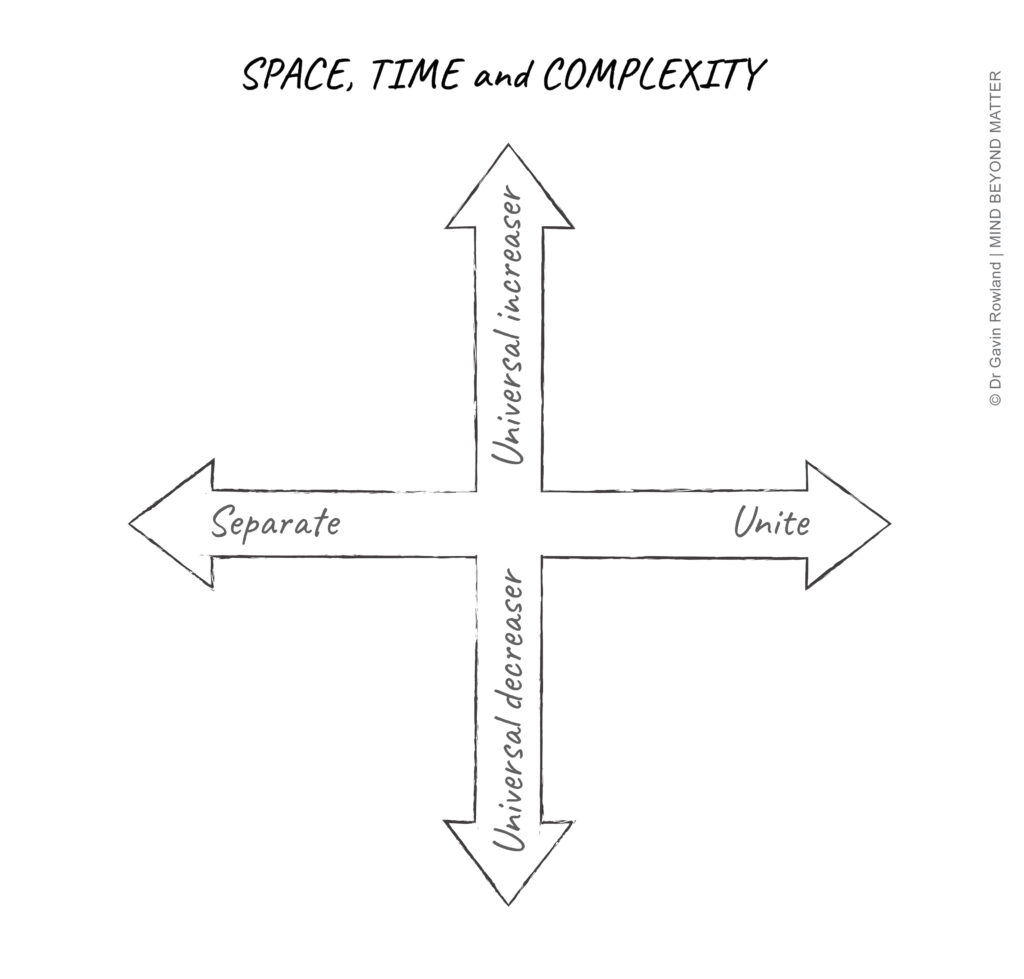

Gravity and this positive energy of matter (call it kinetic or free energy if you like) are bound together as one, in matter. That’s the opposite to the two dark energies, which according to this theory, want to separate via inflation. This leads to the following diagram. DE1 is here called increaser space and DE2 is called decreaser space.

Or if you could take it back a step it becomes even simpler –

Now cosmologists have made very precise measurements of the geometry of the universe, and these measurements indicate that the top and bottom arrows of the above diagram balance out (and hence the universe is exactly ‘flat’). So the net energy sum of the top and bottom arrows may well be zero. If the other two arrows on this diagram, the separating and uniting forces, also balance out to zero, then this could be a universe born from nothingness.

There is a certain appeal in this, as it is a universe that doesn’t necessarily require a creator as it can make its own spacetime and matter, and it’s also a universe that doesn’t necessarily require a preexisting universe. It also fits well with the absolute vastness of the universe. As far as we know the universe goes on forever, and the only way I can think of to create something infinite would be to create it out of nothingness, as there is no limit to the amount of nothingness one could have. Indeed if nothingness were to have some kind of boundary or limit, it would be something rather than nothing.

Of course most of this can’t be proven beyond argument in the way a lot of science-minded people like. So when you propose this kind of stuff you tend to get a lot of argument. That’s just human nature.

Chapter 3 – ‘What’ is a dimension?

In this chapter I argue that in a self-creating universe there should also be mechanism for making the ‘what’ of existence, as existence is ‘what, where and when’, not just a place and time with no subject. I argue that there is a fundamental dimension of ‘whatness’ that has gone unrecognised because it doesn’t conform to what science expects a dimension to look like. That’s because ‘whatness’ isn’t really a measurable quantity. To fit into my theory it should be able to expand towards infinity on one side and contract towards zero on the other. It should be possible to add it to the top and bottom of the diagrams above.

Let us take one example of the subject matter of the universe – a human. There are many layers of complexity here – organs and structure of the human body, cells, molecules, atoms and subatomic particles. All this is built on a set of universal laws and constants that are seemingly finely tuned to allow for the development of such complexity. I argue that these laws and constants are all (with the exception of gravity) signs of this complexity dimension, the results of which, in today’s world, are truly impressive. I also argue that DE1, or increaser space, is probably the ultimate designer of these laws and constants, as it would possess the ability to be conscious. But more of this later.

So without dragging you overly into the detail of the argument, it appears as if complexity as a whole can be added into the cross-shaped diagram of Chapter 2, so that we get the entirety of reality into a form that could fit on the back of a postage stamp:

Note – this is a very brief version of Chapter 3. If you would like something a little more, but not the whole chapter, then try my answer on Quora to ‘Can we explain the fine-tuned universe without religion or parallel universes?’ https://qr.ae/pNsxFo

Chapter 4 – Nonlocality

There are two fundamental problems of physics left – consciousness and quantum physics. But first we need a little knowledge of terminology.

Light generally travels at a standard speed of approximately 300 million metres per second. It can travel no faster. In fact no form of matter can travel faster than this speed limit. In a material world, the speed of light limits the sphere of influence of one event over another. Basically all events that occur within the limit imposed by the speed of light can be termed local. Beyond that, any influence would be nonlocal. This may include events that occur simultaneously in multiple places and events that require backwards in time causation.

So in a purely material world, nonlocal influences could not exist. And yet we see them frequently when we look at the fundamental quantum behaviour of matter. This behaviour is known as quantum nonlocality.

Since its discovery around 100 years ago, there has been huge reluctance from physicists to recognise this nonlocal behaviour. And even though it has been conclusively demonstrated in experiments of recent decades, a lot of misinformation and denial persists. Nonlocal behaviour at the quantum level has often been passed off as “weirdness” and deemed incomprehensible.

But it’s not incomprehensible, it’s just nonmaterial. Nonmaterial because matter can’t behave in these ways, being limited by the speed of light. Each time we take our eyes off a material particle at quantum level, it dissolves into a nonlocal quantum state, only to return to a local state when we take a measurement. This is the phenomenon behind the famous wave-particle duality of quantum physics. The physicist David Bohm referred to this as an “enfolding and unfolding” of information. So information, at the quantum level, appears to pass freely between the material and the nonmaterial. In Mind Beyond Matter I referred to quantum physics as the “meeting room” between the material and the nonmaterial.

Now imagine we have matter floating in a sea of nonmaterial dark energy, and all of this is pervaded by a dimension of “whatness”, constructive in nature. The constructive option would be for the material and nonmaterial to be able to interact in a way that allows them to build complexity in a coordinated fashion, rather than each in isolation. Hence quantum physics.

Interlude – What is science doing?

Dark energy is the first recognised nonmaterial ingredient of the universe. Even now, 25 years after it became part of the standard model of cosmology, I have not seen dark energy mentioned as a possible medium of nonlocal effects. Because nonlocal effects don’t make sense in an exclusively material universe, physicists will often say that quantum phenomena are fundamentally unexplainable. “Shut up and calculate” is a common saying in the field.

Scientists and philosophers alike seem to be restricting themselves to material explanations. This is despite most of the unanswered questions seeming to lend themselves to nonmaterial explanation. Why is this so? Firstly there is the historical success of the material approach. Science has spent so much of its time discovering the details of the material world, it would seem as if matter is all we need to make sense of things. To add to that, scientists have been coming up with material explanations for so long, a lot of the important clues have been obscured by opinions.

If you work downstream of the frontier of fundamental physics and cosmology, perhaps as a philosopher or cognitive scientist, it is logical that you should rely on known and established scientific understanding. So that means the field of explanations in something like consciousness studies is limited to material explanations. That being said, I think in academia in general there is a definite bias against nonmaterial ideas. It seems to be much more permissible to speculate about material causes.

Also important is the system of academic appointment. The majority of jobs in academia have low security of tenure. That tenure is heavily dependent on peer review, and anyone pursuing a career in theoretical physics will be well aware that their advancement is dependent on satisfying the tastes of their superiors. Publications are peer reviewed before being approved, and their success is measured by the number of citations they receive from peers. Grants, prizes, invited talks – all are heavily dependent on peer approval. If senior figures have a bias against nonmaterial explanations, the system increases it’s effects.

Chapter 5 – Consciousness

The core problem of consciousness is how our subjective reality can be created by a material brain. This is variously called the mind-body problem, the explanatory gap or the hard problem. Of course we know that there are various inputs to the brain from the sensory organs – ears, eyes, tongue etc – but there is nothing in the brain’s machinery that leaves us sure that a brain can actually turn all of these inputs into our subjective reality. No-one has ever directly measured consciousness. The best we can find are all kinds of correlates of consciousness within the brain, but these don’t tell us whether the brain actually creates consciousness or whether consciousness is something closely associated with the brain.

I am arguing that consciousness is a product of the dark energy, and that it interacts with the brain via quantum physics. Some of the ground work on how this interaction could happen has already been done by the field of quantum consciousness. It appears there may be innumerable finely tuned ‘levers’ in the brain that could be subject to quantum level information.

There are a number of other questions about consciousness that lead one to a nonmaterial explanation. There is the problem of free will. Local (i.e. material) effects are limited to an endless chain of causes and effects. So a material brain alone may have no more free will than a robot. Nonmaterial agents are not subject to the restrictions of cause and effect and should be able to possess the ability to initiate their own freely willed actions.

There are also problems around how the material brain can create emotions. We will cover these in the next chapter.

So where are the scientists and philosophers in this field at? Most say they think consciousness is hiding in the complexity of the brain or in the fundamental nature of matter. This approach is very limiting, and the field has become rather stagnant. Most new experimental findings relate to quantum level activity in the brain, which is certainly yielding some interesting results.

Interlude – The Laws and Constants

The nonmaterial universe, as imagined by this theory, involves two types of dark energy that repel each other. DE2 (the contracting type) settles out after the Big Bang as pools of eternally contacting space. Like droplets of oil stirred in water, it is immersed in a sea of DE1, the expanding type of space. DE1 is therefore the dominant type of dark energy.

I have also proposed that DE1 should be conscious and constructive. But this consciousness involves a nonmaterial substance only, with no material brain. I would expect this type of mind to be capable of things like infinite foresight, infinite speed of calculation and backwards in time communication. So it should be able to see into the future and create a universe which is finely tuned, as this one is, for constructiveness. Given the quantum interface with which it can create our fundamental physics, I see this as the most likely explanation for the laws and constants.

Chapter 6 – Upward Spirals, Downward Spirals

Here is an excerpt from the beginning of Chapter 6:

“The bible of psychiatric diagnosis is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM. Published by the American Psychiatric Association, the DSM has gone through numerous revisions since its first edition in 1952. At first it primarily categorised psychiatric illness according to Freudian psychoanalytic theories. Then, with the DSM III revision in 1980, it shifted its categorisation to align more with the symptoms. Important categories included – and continue to include – major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and the various anxiety disorders. These categories, and their associated diagnoses, have become enormously useful in clinical practice.

“Essentially the process of DSM diagnosis is based on subjective changes and, in particular, on comparing the mental processes of the patient with those of mentally healthy people. Changes in a patient’s reported mood are common to almost all psychiatric diagnoses. Often the diagnostic categories emphasise psychological distress, including obsessive, pervasive or intrusive thoughts on a particular theme or subject. And within the diagnostic criteria, behavioural abnormalities such as repetitive checking, avoidance or lack of engagement in purposeful activities reflect underlying changes in subjective experience.

“The fact that the diagnosis of mental illness is based on subjective changes shouldn’t be surprising. We are, after all, dealing with mental rather than physical illness. However, psychiatrists have long yearned for a firmer scientific basis for diagnosing mental illness. A common assumption is that psychiatric disorders are essentially brain disorders. There has been, then, an expectation that science will eventually deliver the same insights and benefits that it has with biological disease: separability from other clinical conditions, a common clinical course, well-defined patterns of genetic heritability within families, and diagnostic laboratory tests. And, over the past thirty years, such insights have seen dramatic improvements in treatment and reductions in mortality rates. In conditions such as cancer, diabetes and heart disease, we now have a wealth of treatments targeting the molecular underpinnings of these diseases. But that is with respect to biological disease. In comparison, scientific research into the causes of mental illness has been an abject failure. There was an expectation that the DSM had “carved nature at her joints” (to borrow a metaphor from Plato) and that it had identified a finite number of discrete diseases. But research has failed to detect “zones of rarity” between psychiatric diagnoses. Indeed, it has now become apparent that there is considerable overlap between psychiatric diagnoses, and that at the severe end of the spectrum, multiple psychiatric disorders in the one person is the norm rather than the exception.

“Those charged with formulating the diagnostic criteria of DSM-III and its revisions have found it hard to divide those who should be diagnosed with mental illness from those who should be considered normal. Essentially, the DSM has become a political, legal and economic document. Pension cheques, special schooling and courtroom decisions are awarded on the basis of whether or not the person fits the given criteria in the DSM. Hence the divisions the DSM makes between the normal and abnormal have been made, to some extent, on pragmatic grounds.

“Not all mental illnesses persist in the way that certain physical diseases do. In other words, mentally ill people do not always face the same certainty of deterioration as does the person with say, diabetes or dementia. People’s circumstances in life can improve and psychiatric illness can remit, perhaps occurring again in response to another stressful event.

“In 1999 the American Psychiatric Association convened a multidisciplinary, international effort to formulate the successor to DSM-IV. Frustrated by the nebulous nature of psychiatric illness, and yearning for a scientific footing to put them on a par with their colleagues in the other medical specialties, the association turned to the burgeoning fields of genetics, neuro-imaging and molecular biology for answers. But their hopes for a revolution in psychiatry have been dashed. It was initially hoped that advances in genetics would demonstrate several dominant genes involved in the inheritance of major psychiatric disorders such as depression, schizophrenia and bipolar illness. It now appears that at best there are a multitude of minor genetic influences which do little more than modify, to a mild degree, one’s tendency to develop any particular psychiatric disorder. Research into biological markers (or biomarkers) of mental illnesses has been similarly unrewarding. As of the release of DSM-5 in May 2013, neuroscience has been unable to yield a diagnostic marker for a single psychiatric condition. Professor of Psychiatry and Neuroscience David Kupfer, who chaired the DSM-5 Task Force, says “we’ve been telling patients for several decades that we are waiting for biomarkers. We’re still waiting.””

So on multiple counts mental disorders are quite different from brain disorders. If you have a brain disorder you see a neurologist, or a neurosurgeon. If someone has a mental disorder the specialist they see is a psychiatrist. The psychiatrist may conduct some tests to rule out physical illness, but the psychiatric diagnosis will be made according to a checklist that largely depends on the patient’s own subjective reports of distress. As we lack a biological basis for mental illness, the drugs prescribed by psychiatrists are fairly blunt tools in comparison to those used for physical illness. For example, the so-called antidepressants can also be useful for treating anxiety disorders, post traumatic stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, delusional disorders and bipolar disorder. We don’t know how antidepressants work, and don’t understand what makes one person respond to them better than another. My own feeling is that they act by putting a filter on the delivery of emotional information from the brain to the mind.

So what causes mental illness? Largely it is adverse conscious experiences, and not biological factors. This is particularly the case where individuals who are exposed to stressful situations don’t have the skills or resources necessary to cope, such as where children are subjected to abuse. A large proportion of adult mental health disorders are thought to be directly attributable to childhood abuse. This connection is present across the entire spectrum of mental health issues.

I don’t discount biological causes entirely. I am a medical practitioner of the mainstream type, and commonly prescribe medications for mental illnesses. The following model presents mental illness as an interplay between the brain and a nonmaterial mind, comprised of two types of ‘dark energy’. So there is still scope for causative biological factors, and for biological treatments.

And before we start, a few words about emotion. Emotions come in two general flavours – positive and negative. Positive emotions include joy, love and happiness and negative emotions include depression, anxiety and anger. The term valence is used in psychology when we talk about the positive or negative charge of an emotion (or piece of emotionally charged information). So sadness has negative valence and joy has positive valence. The terms emotion and affect are basically interchangeable.

There is a bipolar spectrum of emotion from strongly negative, through neutral states to strongly positive. Hence the term bipolar affective disorder where people can swing between the extremes of affect. Emotions provide a key ‘flavour’ to our conscious experiences. These flavours are so integral, they can dictate and distort or experiences. One problem with the current, brain-based theories of consciousness is that they make little attempt to explain emotion. There is very little beyond a nod to brain biology and evolution.

Now instead of imagining the mind as the product of a lump of grey matter, imagine it as a mixture of the two dark energies. One is constructive, the other destructive. The constructive one also has spacetime effects – speeding time and expanding space – and we can study consciousness to see if these effects are also present. The destructive one slows time and contracts space.

When positive emotions predominate, consciousness has been shown to have the following properties – time speeds up, the field of attention broadens and our thoughts become more constructive. When negative emotions predominate, we feel as if time drags, the field of attention narrows and our thoughts become destructive. The mind is also drawn towards thoughts of like valence – when happy we see the glass half full, but half empty when we are feeling down. The effects of prolonged negative emotions are varied, but tend to create narrowed possibilities in life, vulnerability to stress and further downward spirals. In contrast, prolonged positive emotions tend to build relationships and skills, leading to greater success in life and resilience to stress.

These patterns are consistent with destructive and constructive mental energies working dynamically in opposite directions. As I see it, the predominant valence of mental energy will dictate the emotional direction of the mind, be it positive or negative. Broadly speaking, the predominant mental energy depends on two things. Firstly, everyone tends to have a “set point” along the positive-negative spectrum towards which their underlying mood will trend. This has a lot to do with their formative emotional experiences in childhood. Secondly, their mood can be influenced by emotional factors in their current environment.

This is why mental illness can be influenced at the level of consciousness, where brain diseases cannot. I would be practicing good medicine to prescribe counselling for depression, but would be practicing bad medicine if I attempted to treat someone’s stroke or brain tumour with counselling. Supporting someone through their experiences, reframing events in more positive terms and helping them to understand and hope again are all ways of introducing positive information to the mind.

So what are the implications of this model for the question of free will? These days, the majority of scientists and philosophers are either claiming that free will is an illusion, or that the brain alone can give us free will. I disagree with both these viewpoints. As I said previously, only a nonmaterial mind can give us free will. But the type of freedom we have in this model is dictated by our emotional state. This takes us back to the age-old discussion of reason versus the passions, now more commonly described as the interplay between cognition and emotion. If my mind has a healthy positivity, the evidence says that I can see myself and my options with a mild positive bias. I can see the big picture as my awareness as broad. This is what most people would associate with freedom of choice.

But if a mood is very negative, the attention narrows severely and the only thoughts available to consciousness are negative. In this model this is because the negative headspace can only entertain ideas with a negative emotional valence. Psychologists spend a lot of time trying to arm patients with the tools necessary to cope with such situations – the panic attack, the fit of blinding rage, the dark pit of depression that leaves the mind consumed with pain and looking for an outlet. But often the known strategies of escape are obliterated by negative tunnel vision as well. In these situations the scope of free choices are very limited. I have come across plenty of people who were unsympathetic to people with the consequences of mental health issues. They might say “they brought it all upon themselves.” This is one of the many unhappy consequences of our lack of understanding of consciousness.

Two other issues that are poorly addressed by any material model of consciousness are evil and altruism. In both cases we need to look at the impact of emotional valence and realise that the mind is a representation of our reality. My skin is my skin, my liver is my liver, but my mind is my inner world as well as a representation of my environment. So if my mind is poisoned by excesses of negative emotion, I have two broad options. I can internalise my negative emotion and experience anxiety, depression and so forth. Or I can externalise that negativity and seek to displace it in a place that is less painful to me. The so-called externalising behaviours include substance abuse, vandalism and the abuse of others. A common feature at this severe end of this spectrum of mental illness is a narcissistic, inflated self esteem, which also serves to protect the self from any inner experience of psychological pain.

The opposite of this scenario is altruism. Again, brain based theories have this wrong, I think, arguing that altruism is a feature of humans and animals for evolutionary reasons. I see it like this – if my mind is mainly positive mental energy, I will want to see not only myself but also my surroundings full of positive information. So I will strive to look after others and try to bring those who are struggling up to my level.

Of course, having covered evil and altruism we have also covered much of the question of morality. Chapter 6 also includes a discussion of positive psychology, and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of flow. Flow involves seeking positive experiences by immersing oneself in a constructive process.

Chapter 7 – Implications

The concept of meaning and purpose are discussed in light of a model that sees flourishing mental health as an abundance of constructive mental energy. I discuss the idea of information hygiene, and look at the bigger picture of mental health and illness. I also explore psi experiences, mystical experiences and near death experiences. These types of experience are looked upon with great scepticism by those who regard the mind as a material thing. For this reason, people tend to keep these experiences to themselves. Finally I discuss the question of God, and look upon it favourably (see also above Interlude – The Laws and Constants).